Will technology temper the climate chaos in our wine?

TOASTY OAK, SCORCHED EARTH, ROASTED COFFEE BEAN AND SMOKE…Once used to describe some barrel-aged wines, the descriptive term “smoke” has come to mean something far more literal since the turn of the century — the smell and taste of actual smoke.

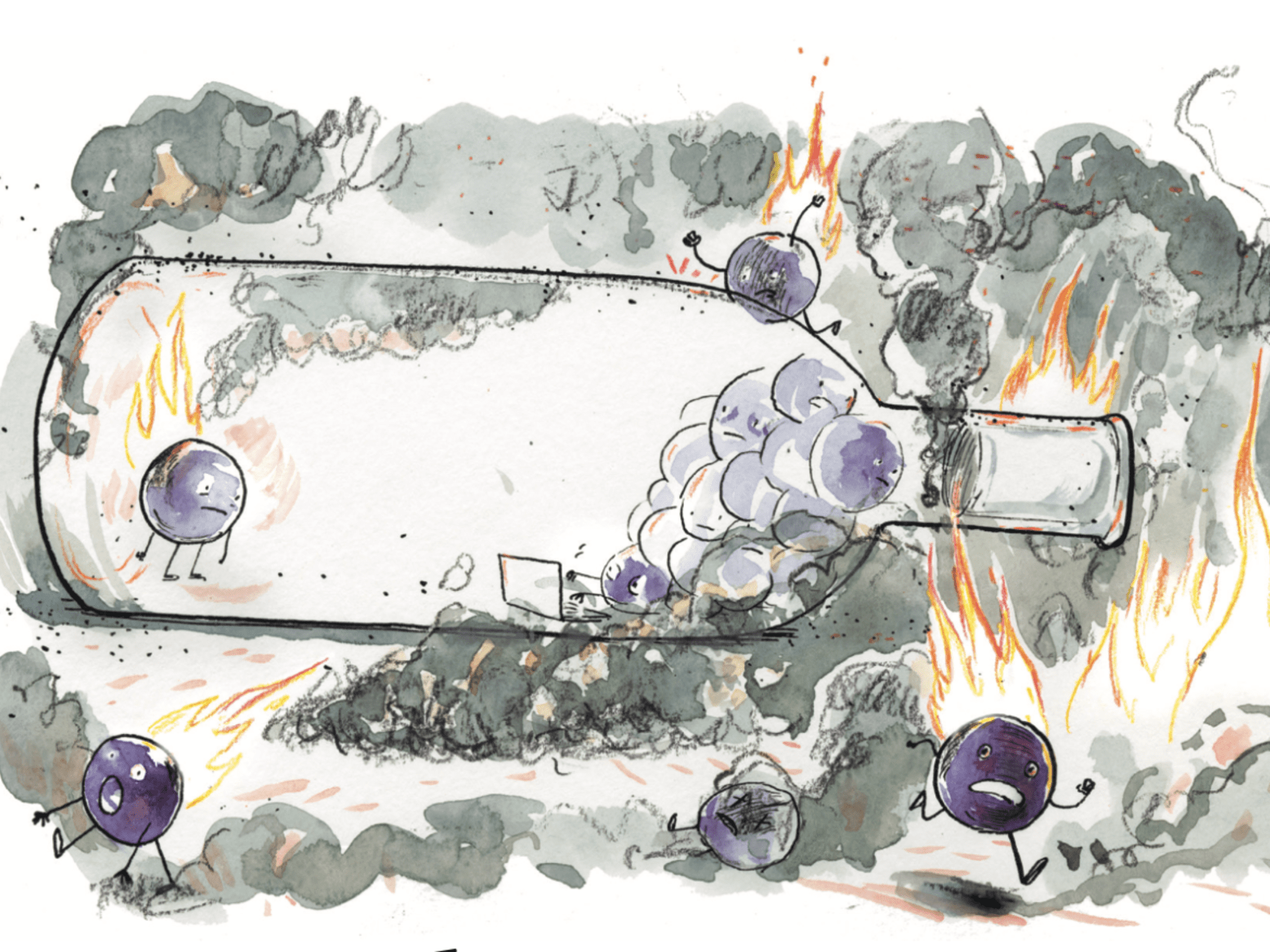

Wildfires of greater frequency and intensity are the 21st-century scourge of the wine industry. The Pacific Northwest, Australia, South Africa, Greece, France and Italy, among others, have all experienced harvest-threatening wildfires in the last five years. It’s not just the fire itself that brings peril, but, more problematically, the smoke it generates and the aroma that leaves behind. The problem thus of wines that smell and taste of actual smoke — “smoke taint,” as it’s known in the industry — is not trivial. Millions of dollars worth of wine have been lost or sold to unsuspecting consumers.

For the record, declaring that a wine is “smoke-tainted” can be complicated. Smoke compounds, called volatile phenols, can occur naturally in wines made without a fire in sight, barrel-aged wines especially. It’s also unfair to write off an entire region where a wildfire occurred. Taint or no taint depends, literally, on which way the wind blows. It also depends at what point in the season the fire strikes — close to harvest (when wildfires are likely to occur) is the most problematic, as the “fresher” the smoke, the greater the impact. Smoke compounds oxidize and degrade in sunlight over time and become less potent. And while there’s no “safe” distance from a fire, the farther away it is, the more dilute the smoke compounds will logically be when they reach the vineyard.

It is also worth knowing that the compounds that cause taint come mainly from grape skins, so red wines are much more frequently affected than whites or rosés, which undergo little or no skin maceration.

But at high levels, once you are familiar with it, the smell is unmistakable. It ruins wine.

Researchers are urgently working to understand the smoke problem and find ways to prevent or mitigate the nefarious effects. So-called barrier sprays, such as bentonite or kaolin clays, applied to vines prior to expected smoke exposure effectively reduce berry uptake of smoky compounds by…creating a barrier.

Techniques to remove volatile phenols have also become more sophisticated. One promising technique not yet officially approved uses molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) to attract and bind the unwanted smoke molecules, reducing them to very low levels, like the egg-white raft that clarifies a consommé.

Reverse osmosis is the most widely used technique. It involves separating wine into essential components, removing the ones you don’t want (volatile phenols), then putting the rest back together again. It’s been used to reduce alcohol, for example, for many years now. But the process involves an expensive machine and also “beats up” the wine, leading to premature aging. Filtering with activated carbon is also effective, though its impact on wine quality is even more severe, stripping out the good with the bad.

In the end, the good news is that the understanding of smoke taint — how to analyze for it, how it gets into berries, and which factors exacerbate or mitigate its impact — is deepening daily. Short of finding a way to prevent wildfires, these latest techniques are our best hope of smoke-taint-free wines.

By John Szabo MS