Especially when your ancestors were smart enough to put down stakes in the 1730s.

Fresh off the two-hour drive north from Lyon, my wife Lisa and I breezed through the quiet town centre of Beaune and pulled up at the 17th-century mansion at 18, rue des Tonneliers, HQ of Maison Louis Latour. The courtyard was picture-perfect, down to some recently planted pansies, still in bloom, defying the late January chill. Inside, export director Mark Allen was ready and waiting for us to explore the glory in Burgundy wines.

With our scheduled lunch an hour off, we got started upstairs in a beautiful sitting room, with a revivifying espresso and a quick briefing. As you likely know from its familiar label, Maison Louis Latour was fondée en 1797. But the Latour family’s involvement with winemaking in Burgundy actually predates that. They were growers in Côte de Beaune from the early 1730s, and by 1768 had begun acquiring vineyards on and near the coveted Hill of Corton. It all went well enough that in 1867 they could purchase the négociant Lamarosse Père et Fils (along with their offices—the grand house on rue de Tonneliers). And in 1890, when Phylloxera had the Comte de Grancey on the ropes, Latour picked up Château de Corton Grancey too. A decade on, it collected holdings in Chambertin and Romanée-Saint-Vivant.

And so things progressed in fits and starts to the present day, when Maison Louis Latour—still family-owned—finds itself the largest landowner of grand cru property in the Côte-d’Or. Expansion can only happen elsewhere now, and in that regard, Latour enjoys a second notable distinction from its local counterparts. While so many of them have of late (well, starting in 1987, when Robert Drouhin of Maison Joseph Drouhin established Domaine Drouhin Oregon) satisfied their need for expansion by setting up shop in the familiar terroir and climate of the Pacific Northwest, Maison Louis Latour has instead elected to stay home. All of its new ex-Burgundian ventures have been launched in less rarefied French wine-growing regions, from Le Var (in Provence) to the Ardèche and Beaujolais.

“As Louis-Fabrice likes to say of his wineries,” said Mr. Allen, speaking of his boss Louis-Fabrice Latour, the 11th member of his family (and seventh Louis) to have helmed this venerable business, “‘If I can’t be there before lunch, it’s too far away.’”

It suddenly seemed doubly unfortunate that Monsieur Latour was abroad on the occasion of my visit, for obviously he and I saw eye-to-eye on more than a few things: the bane of unnecessary travel and the importance of lunch, not to mention the general primacy of Burgundy in the pantheon of wine.

On which note the time had definitely come to try some. I hadn’t had any since dinnertime in Lyon the night before. As luck had it, Mr. Allen had arranged for a pre-lunch tasting of a representative array of Maison Latour’s burgeoning offering, so we promptly decamped to a dining hall downstairs where the bottles awaited us, arranged in rows of reds and whites on a grand table.

No doubt you are familiar with Latour’s perennial best-sellers—their flag-carrying entry-level, varietal-labelled chardonnay and pinot noir. Less likely you’ve sampled an exquisite 2015 or ’16 vintage of a Latour 1er Cru Meursault or Aloxe-Corton, or Grand Cru Charlemagne or Corton. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

To start, we sampled a 2017 Chablis from Latour’s Maison Simmonet-Febvre, nicely balanced with notes of citrus (lime and grapefruit) and sound minerality. Then we moved to their 2016 Chablis 1er Cru “Vaillons.” A more challenging year, with still more punishing fruit loss to frost and hail, but what survived was worth the trouble (lovely fruitiness and floral notes, nicely balanced with strong minerality). Next, we tried Maison Latour’s 2017 chardonnay, the workhorse and baseline in their stable of whites, and—continuing our tasting journey southwards—landed in the Mâcon, with Latour’s 2017 Mâcon-Lu- gny “Les Genièvres,” which had a seductive bouquet of pineapple and honey. Next, a divine 2016 Meursault 1er Cru “Château de Blagny,” a vineyard overlooking Puligny-Montrachet, which had notes of pear and apple and a delightful finesse. Then we got to 2015 Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru, which—convention be damned—I simply could not bring myself to dump unfinished into the spittoon.

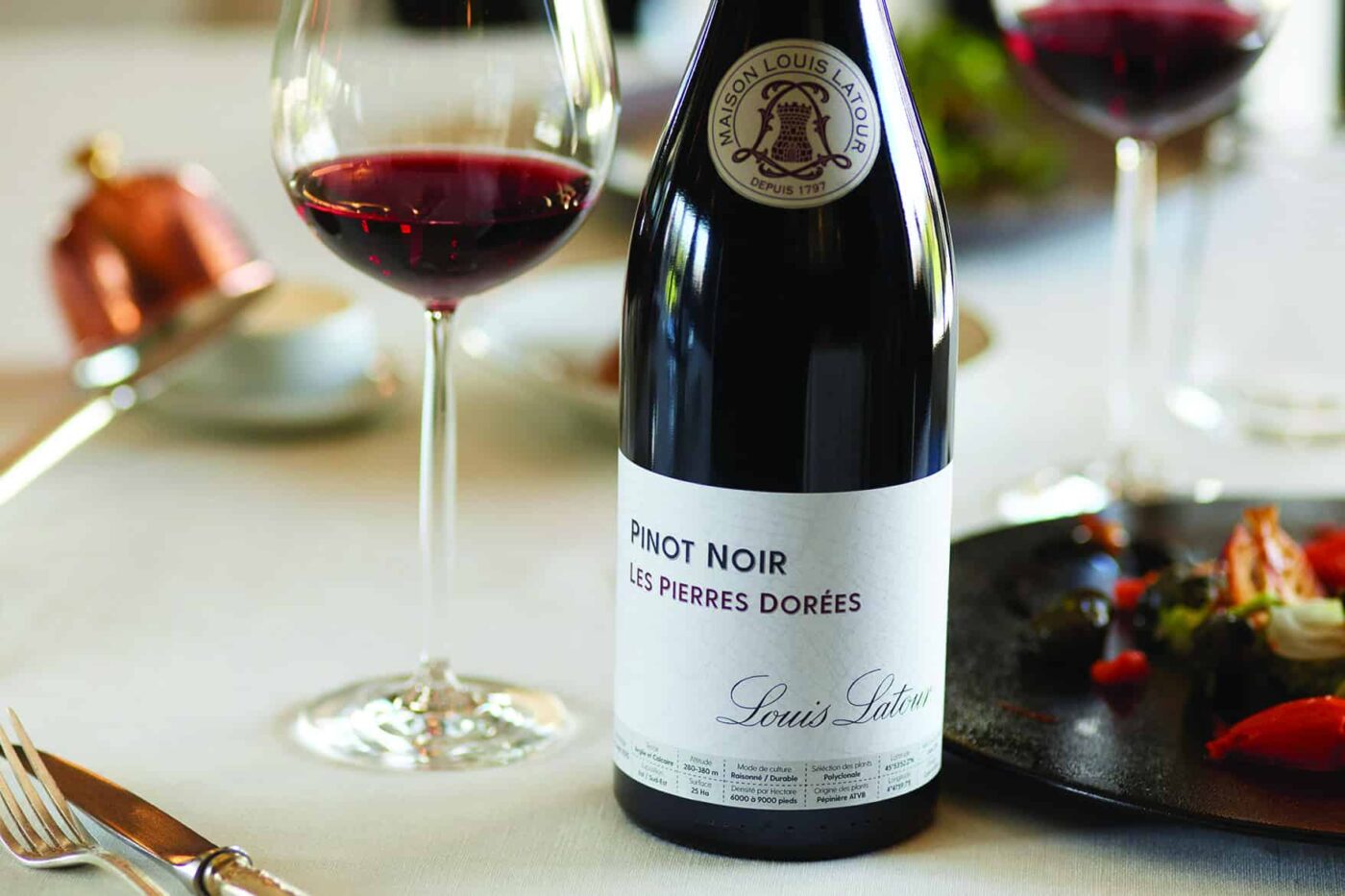

On that high note, we left chardonnay behind us and soldiered on through the reds, dabbling first in some fruity, red berry-rich gamays from Latour’s Maison Henry Fessy, in Beaujolais. From there we veered to Latour’s latest project, a Latour-labelled Beaujolais-grown 2017 Pinot Noir “Les Pierres Dorées,” fruity and soft, but with complexity in its aromas. This was just the third vintage from a freshly planted 20-hectare vineyard some 40 kilometres outside of Lyon—a location that was by local custom unconventionally southern for that varietal, albeit cooled by virtue of altitude (the elevation runs from 280 to 400 metres). Then it was time to venture into the opposite end of Latour’s historical spectrum (in location, not vintage) with an elegant 2016 Aloxe-Corton 1er Cru “Les Chaillots” and then to finish with still more finesse, a 2016 Corton Grand Cru “Clos de la Vigne au Saint.”

“People will talk about 2016 for a long time,” ventured Maison Latour director Christophe Deola, who had just joined us in the tasting room and was catching up swiftly. “2015 might be sexier, more luscious. But 2016 is more intellectual…”

Even when spitting (OK, mostly) and not imbibing, there is definitely a limit to how many wines I can taste before lunch. Eventually, I arrive at a point of capacity, where flavours and nuances grow less assertive, begin to mingle and grow muddled. I was there; this talk of intellectual vintages was lost on me. It was time for some food.

So we settled in upstairs for a classic Burgundy lunch (oeufs en meurette, a favourite of mine, followed by roast pigeon and poached pear with chocolate) and then we went off on a drive, heading northeast out of Beaune. We made our way through local vineyards, aiming for Corton, the grands crus and premiers crus in the small hills to the west on our left, and the appellations communales stretching out in the flat land to our right. Twenty metres, maybe less, divides them. What’s in the soil beneath, unseen, is the major part of that story. So is exposure, and temperature. And if you don’t think it can vary that much over these seemingly insignificant elevations, nothing illuminates the subject quite like a visit to the Côte-d’Or in January, when the tops of these small 200-metre-high hills are dusted with snow while beneath, everything is bare.

Global warming is obviously a factor here, as the warmer summers provoke riper wines, while more frequent weather disturbances like early frosts and hail have wreaked havoc on innumerable recent vintages. Yet 2017 was smooth sailing, and prices for premium Burgundies keep escalating, driven by soaring demand in long-established markets and the new, overwhelming Asian market. A visit here shows that the real issue is size. These appellations—from Montrachet to Meursault, Corton and Chambertin—all loom so large in the imagination, but in reality turn out to be the size of postage stamps. The Burgundians are definitely making the most of things.

[vc_masonry_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1563316098054-44e514c4-eb2a-3″ include=”20957″]

A CONVERSATION WITH LOUIS-FABRICE LATOUR

C100B: Your company dates back to the First Republic and has endured unthinkable historical upheavals since—all under uninterrupted family control. How does that legacy inform your decisions today?

Louis-Fabrice Latour: A few years after the revolution we were allowed to buy some land. We started in Aloxe, as winegrowers. Little by little, we expand- ed. We survived wars, and Phylloxera. Sometimes we were growers and some- time négociants. We speak French—and sometimes we spoke German. It is actually a very classic business story around here. What I take from the history is more about the standards. We should make good wine in a classic way. This is what I make sure we always do—make wine that is well-balanced, with finesse.

C100B: Maison Latour is known for tradition and innovation both. How does the “les Pierres Dorées” initiative fit into this context?

LFL: We are the only producer here not to go to Oregon. I thought Beaujolais was a good idea. The decision to try its southern part was based on terroir. There is lots of limestone and clay, and nice slopes facing south and southeast.

It’s been 10 years now. We planted 20 to 25 hectares. It was a daring project when we started. I was very anxious about the quality at the beginning; I’m very confident about it now. There are maybe 2,000 to 3,000 more hectares where the soil is exactly right for pinot noir, and I invited my friendly competitors to have a look because there’s room for everyone. In Burgundy, with global warming, we need to take initiatives. Warming does not mean that you must go north. We say go south, but you must also go up! Instead of planting at 200 or 250 metres, we plant at 280 to 400 metres.

C100B: And why not just go to Oregon, like your peers?

LFL: Like my father, I wanted to remain in France. We always believed that we should stick with what we know. We don’t know syrah or cabernet sauvignon. We know pinot noir and chardonnay. So we aim to innovate but to do so in France. With my father, in the 1970s, that meant planting chardonnay in the Ardèche. And in the ’90s it meant pinot noir in Var. As I like to say, never invest in a place you cannot get to in time for lunch. It cannot be more than a three- or four-hour drive away.

C100B: In Canada, more people know Maison Louis Latour because of its varietal-labelled entry-level wines than for its 1er or grands crus. How do you summarize the brand to consumers baffled by its range?

LFL: It should not be confusing. You must remember that 50 per cent of the wine produced in Burgundy is regional appellation. It is very important to make a regional appellation in the regional style. Nobody is drinking Aloxe-Cor- ton, Meursault and Gevrey-Chambertin every day. But we are the biggest Domaine in Corton. We aim to show more and more that we make these large wines of great complexity. Our Corton is world-renowned, but people should not drink it every day. It is the other wines of Maison Latour that are there to help people discover the pleasures of Burgundy.

Share: Facebook, X (Formerly Twitter)