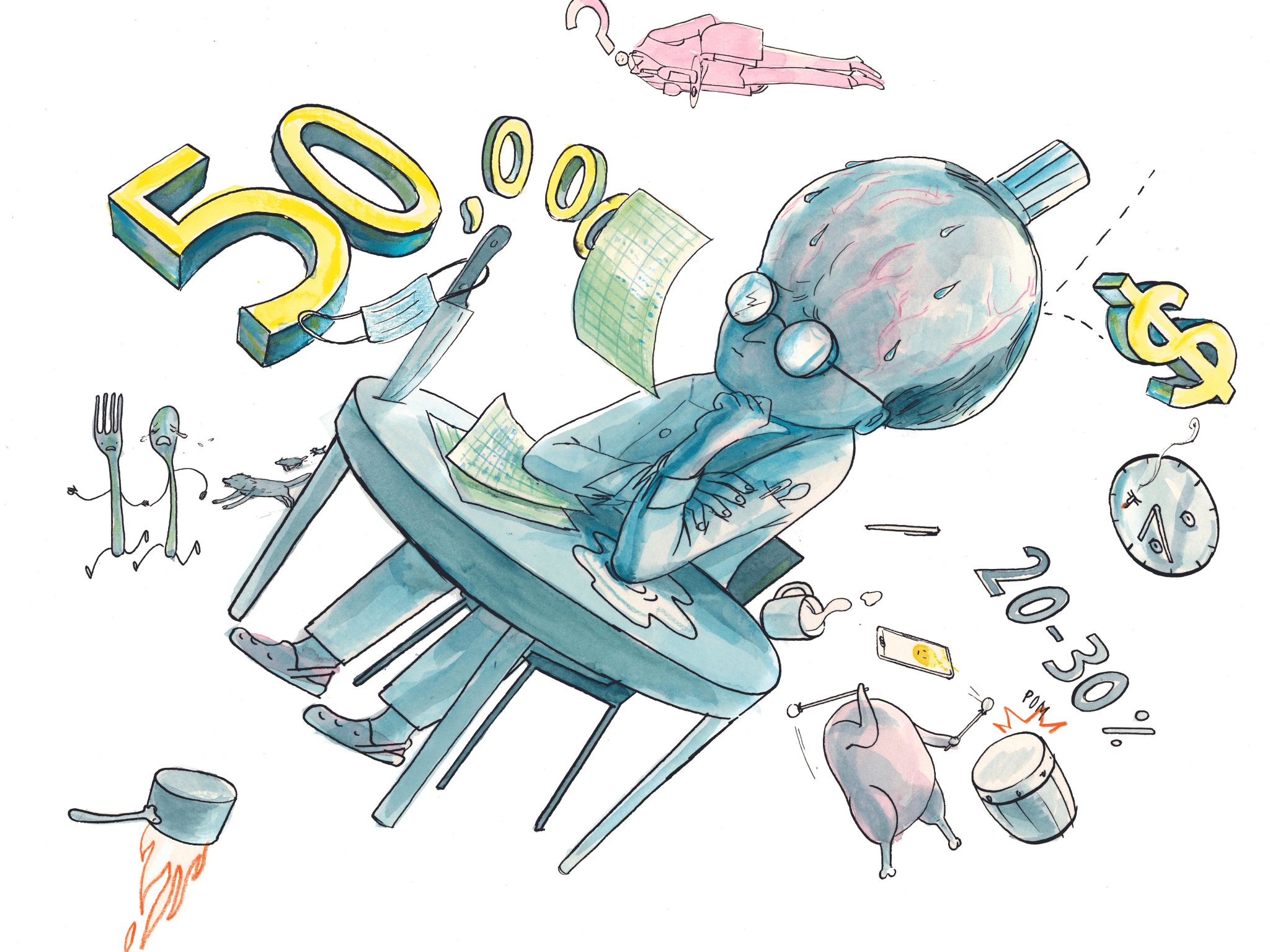

THANKS TO VACCINE PASSPORTS, restaurants are beginning to return to normalcy, but they are still a long way from being out of the woods. Along with the lingering pandemic, restaurants are also dealing with rising food prices, supply chain issues, severe labour shortages, and new challenges, like food delivery and its associated new costs. Conventional restaurant business math has become increasingly difficult to apply.

Before the pandemic, the most fundamental rule of restaurant profitability revolved around the cost of food products — that is, it should not exceed 30 percent of the revenue they generate. If you were a smart restaurateur, you’d get that cost down to 25 percent. If the wholesale price of your raw chicken breast and its sauce components and side added up to $5.75, you had better charge $20 if you wanted to survive — and $23 if you expected to one day drive a decent car. But now, even that basic math is not quite viable, and less so for high-end items.

“People still want their lobster and Dungeness crab, so all of those expensive things will still be there and, more than likely, going up in price, relative to what we’re getting charged from the supplier,” says chef David Hawksworth of Hawksworth Restaurant in Vancouver. “Whatever happens down the chain, then we’ll redo the math. You might not see an increase or you might see a 25-per-cent increase.”

While restaurants may increase the price of some menu items, they’ll also need to balance that out by perhaps swapping in a few cheaper items — like cod instead of halibut — or risk losing customers. Or they can search out other efficiencies. Hawksworth, for example, is considering a more “rigid” menu to discourage customer-requested substitutions as a way to control costs — and ease the burden on the back of house, already struggling with a labour shortage.

“You have to be more creative with how you’re handling things,” Hawksworth says. “Portion sizes might get a little bit smaller, [perhaps opt for] more vegetables and a little less protein. It’s tougher if you’re a protein-forward restaurant because at no point will a meat supplier say things are going down in price.”

Supply chain issues have increased shipping costs while making it more difficult for restaurants to get the ingredients they need. Erratic demand has prompted suppliers to reduce inventories.

“Expect another 8- to 12-per-cent increase for food in the next year,” warns chef Michael Allemeier, a culinary instructor at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology.

Menu engineering is one way to offset rising food prices while maintaining the 30-per-cent benchmark for food costs, according to David Cleary, a professor in George Brown College’s culinary arts program — “whether that’s increasing the sales price for a really awesome product that sells often or decreasing portion sizes where applicable.”

Tracking customer waste to find where portion sizes can be reduced without impacting customers is an option. “But if restaurants are using a lower-quality cut of meat but still charging the same price, the custom- er’s perceived value of the meat starts to diminish,” notes Cleary. That, in turn, impacts customer loyalty.

“I don’t know how much more the market can bear in terms of the guest paying more for food,” says Allemeier. “If the price of oil goes up, the price at the pumps goes up. We grumble, but everybody pays it. We don’t have that same mentality for restaurants. Delivery, labour, and ingredients have all gone up, but it is very hard for operators to increase menu prices, especially now with high unemployment rates.”

Subsidies have helped, but the math will change once again as they subside. “We still have all of our fixed expenses [and] we can’t run at 100 percent because we don’t have enough staff. So, you’re making less but you still have all the risk,” says Hawksworth. “I guess I’ll be able to retire in my next life.”

By Vawn Himmelsbach